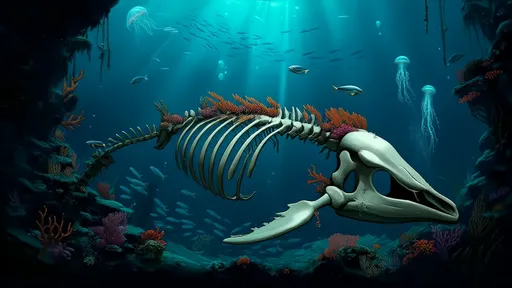

In the crushing darkness of the deep sea, where nutrients are scarce and life is a constant struggle, one of nature's most profound and paradoxical cycles unfolds. It begins not with a birth, but with a death. The descent of a whale carcass—a phenomenon poetically termed a 'whale fall'—creates a sudden, concentrated oasis of organic matter on the barren seabed. This event triggers a complex, decades-long ecological succession, transforming a site of death into a thriving hub of biodiversity and a remarkable case study in deep-sea sustainability.

The journey of a whale fall starts miles above, at the ocean's surface. When a great whale dies, its massive body, a reservoir of energy built over a lifetime of feeding in the productive sunlit waters, begins its final voyage. Sinking through the water column, it eventually comes to rest on the seafloor, often at depths exceeding a thousand meters. The impact is nothing short of an avalanche of riches in a food-desert. This single event deposits more organic material than would typically rain down from above over centuries, creating a localized ecosystem that sustains life for fifty to a hundred years.

The ecological succession on a whale fall occurs in distinct stages, each characterized by a changing cast of species that exploit the carcass in different ways. The initial phase, the mobile-scavenger stage, is a frenzy of activity. Large and highly mobile deep-sea organisms, like sleeper sharks, hagfish, and gigantic amphipods—the vultures of the deep—descend upon the soft tissue. They can strip a carcass of its blubber and muscle down to the bone in a remarkably short period, sometimes mere months. This stage is a violent and rapid redistribution of energy, but it is only the beginning.

Once the scavengers have had their fill, the scene shifts to the enrichment-opportunist stage. This phase is dominated by a denser, smaller, and slower-moving community. Polychaete worms, crustaceans, and other opportunistic species colonize the bones and the surrounding sediment, which has been enriched by the scattered bits of flesh and nutrient-rich waste from the initial scavengers. These species are specialists in exploiting concentrated organic matter, and their populations bloom dramatically, creating a writhing carpet of life on and around the remains.

The longest and most fascinating phase is the sulphophilic (sulphur-loving) stage. This is where the true alchemy of the whale fall occurs. The lipids oils trapped within the massive skeletal structure are broken down by anaerobic bacteria deep inside the bones. These bacteria utilize sulfate from the seawater in their metabolic process, producing hydrogen sulfide as a waste product. This hydrogen sulfide, toxic to most life, becomes the foundation of a chemosynthetic ecosystem, mirroring the famous hydrothermal vents.

Specialized bacteria that can chemosynthesize—using the chemical energy from hydrogen sulfide to create organic matter—form the base of this new food web. They colonize the bone surfaces and the surrounding sediment. In turn, they support a diverse and exotic assemblage of life, including mussels, clams, tube worms, and limpets that have evolved symbiotic relationships with these bacteria. These organisms are not filtering food from the water or feeding on detritus; they are thriving on the chemical energy released from the very bones of the whale, a process that can sustain a complex community for decades.

The final stage is the reef stage. After decades of consumption, the bones, depleted of their organic content, begin to degrade. What remains is a mineral-rich structure that can provide a hard substrate for suspension feeders like corals and sponges to attach themselves. This final act transforms the whale fall from a nutrient-based oasis into a structural reef, contributing to the three-dimensional complexity of the deep-sea floor and providing habitat for yet another community of organisms long after the original nutrient pulse is gone.

The sustainability of these deep-sea oases lies in their cyclical nature and their role in nutrient cycling. The deep ocean is largely cut off from the primary production of the sunlit surface layer. The constant "marine snow"—a slow drizzle of decaying organic material—provides a minimal baseline of food. Whale falls shatter this limitation. They are massive, pulsed inputs of energy that bridge the ecological disconnect between the productive surface and the impoverished deep. By efficiently recycling a colossal amount of biomass in situ, they prevent this energy from being lost and instead distribute it through the deep-sea food web over an extended period.

This process represents a highly efficient and natural form of resource management. Every part of the whale is used, from the soft tissue to the bone marrow. The succession of species ensures that there is no waste; each guild of organisms specializes in unlocking a different fraction of the carcass's energy, passing it on to the next. The system is self-contained and self-sustaining for the duration of the fall's existence, operating on principles of maximum efficiency that any human system would envy.

Furthermore, whale falls serve as evolutionary stepping stones. Scientists hypothesize that the chemosynthetic ecosystems found on whale bones may have acted as refuges and training grounds for species that later colonized other chemosynthetic environments, such as hydrothermal vents and cold seeps. The falls create interconnected nodes of life across the vast and otherwise inhospitable abyssal plains, allowing for gene flow and species dispersal. This enhances the overall resilience and biodiversity of the deep-sea biome, making it more robust against environmental changes.

However, the sustainability of this deep-sea miracle is not guaranteed. It is intrinsically linked to the health of whale populations in the upper ocean. Centuries of commercial whaling decimated global whale populations, and while some species are recovering, they face new threats from ship strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, and the overarching impacts of climate change and ocean acidification. Fewer whales mean fewer whale falls. The deep sea, already facing pressures from deep-sea mining and pollution, risks losing these critical oases, which would have cascading effects on its biodiversity and ecological function.

Understanding and protecting whale falls is, therefore, not merely an academic curiosity but a conservation imperative. They stand as a powerful testament to nature's ability to create sustainable, zero-waste systems that support immense biodiversity even in the most extreme environments. The whale's journey does not end with its death; its body becomes a cornerstone for life, a final gift that sustains a hidden world for generations. In studying these深海绿洲 (deep-sea oases), we find a profound lesson in circular economy, resilience, and the interconnectedness of life from the surface to the seafloor.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025