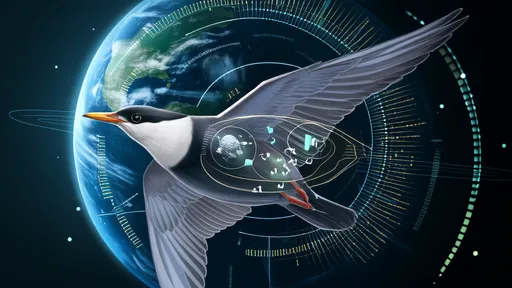

In the evolving landscape of materials science, the study of structural biomaterials has emerged as a pivotal field, bridging the gap between biological systems and engineering innovation. This discipline, often referred to as structural biomaterials science, delves into the intricate architectures and properties of natural materials, seeking to harness their unique characteristics for advanced technological applications. From the resilient silk of spiders to the robust nacre of abalone shells, nature offers a treasure trove of inspiration, demonstrating solutions to complex engineering challenges that have been refined over millions of years of evolution.

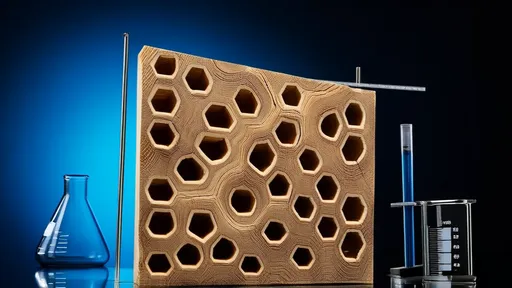

The fundamental premise of structural biomaterials lies in understanding how biological entities achieve remarkable mechanical properties through hierarchical structures, often composed of relatively simple and abundant components. For instance, wood, a common natural material, exhibits exceptional strength-to-weight ratios due to its cellular composition and alignment of cellulose fibers. Similarly, bone combines inorganic minerals with organic collagen to create a composite that is both tough and lightweight. These natural designs not only optimize performance but also emphasize sustainability, as they are typically biodegradable and produced under ambient conditions.

One of the most celebrated examples in this domain is spider silk, renowned for its unparalleled tensile strength and elasticity. Researchers have long been fascinated by this material, which outperforms many synthetic fibers on a weight basis. The secret lies in its protein structure, where molecular alignment and hydrogen bonding contribute to its mechanical prowess. Engineering applications are vast, ranging from lightweight protective gear and medical sutures to advanced composites in aerospace. However, replicating spider silk synthetically has proven challenging, prompting innovative approaches such as recombinant DNA technology and biofabrication methods to produce scalable quantities without relying on spiders themselves.

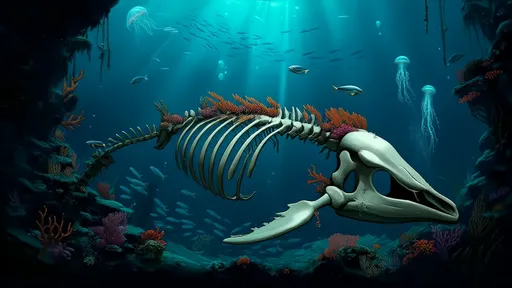

Another intriguing natural material is nacre, or mother-of-pearl, found in the inner shells of mollusks. Its brick-and-mortar microstructure, consisting of alternating layers of aragonite platelets and organic proteins, confers exceptional fracture resistance and toughness. This structure has inspired the development of synthetic composites for applications requiring impact resistance, such as body armor, automotive components, and even flexible electronics. By mimicking nacre's design, engineers have created materials that dissipate energy efficiently, preventing catastrophic failure under stress.

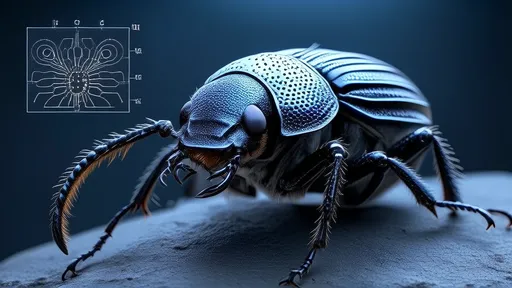

Beyond these well-known examples, lesser-known biological materials like byssal threads from mussels and the adhesive properties of gecko feet offer insights into advanced bonding mechanisms. Mussel byssus, for instance, exhibits self-healing capabilities and strong adhesion in wet environments, inspiring new types of underwater adhesives and coatings. Gecko feet, with their nanoscale hair structures, demonstrate reversible adhesion through van der Waals forces, leading to innovations in robotics and climbing devices. These natural systems highlight the potential for creating multifunctional materials that adapt to their environment.

The engineering applications of structural biomaterials extend into the realm of sustainability and environmental responsibility. As the world grapples with plastic pollution and resource depletion, bio-inspired materials offer a path toward greener alternatives. For example, mycelium-based composites, derived from fungal networks, are being developed as biodegradable packaging and construction materials. Similarly, chitosan, derived from crustacean shells, is used in water purification and biomedical applications due to its antimicrobial properties. By learning from nature, engineers can design products that are not only high-performing but also environmentally benign.

In the medical field, structural biomaterials have revolutionized implantology and tissue engineering. Natural materials like collagen and hydroxyapatite are integral to bone grafts and scaffolds, promoting cell growth and integration with host tissues. Researchers are also exploring silk-based platforms for drug delivery and wound healing, leveraging its biocompatibility and tunable degradation rates. These advancements underscore the synergy between biological understanding and engineering precision, leading to improved patient outcomes and reduced rejection rates.

Despite the promise, translating natural designs into practical engineering solutions is not without challenges. Scaling up production while maintaining the intricate hierarchical structures found in nature remains a significant hurdle. Additionally, the variability inherent in biological materials can complicate standardization for industrial use. However, advances in nanotechnology, additive manufacturing, and computational modeling are accelerating progress, enabling more precise replication and customization of bio-inspired materials.

Looking ahead, the field of structural biomaterials is poised for exponential growth, driven by interdisciplinary collaboration among biologists, chemists, physicists, and engineers. As our understanding of biological systems deepens, so too will our ability to emulate their genius. This convergence of nature and technology holds the key to addressing some of humanity's most pressing challenges, from sustainable manufacturing to healthcare innovation. Ultimately, structural biomaterials represent not just a scientific endeavor but a philosophical shift toward harmonizing human ingenuity with the wisdom of the natural world.

In conclusion, the study and application of structural biomaterials underscore a profound appreciation for nature's engineering prowess. By decoding the secrets of biological materials, scientists and engineers are unlocking new possibilities for innovation across diverse sectors. From spider silk to nacre, these natural wonders inspire a future where materials are stronger, smarter, and more sustainable. As research continues to advance, the boundary between the natural and the engineered will blur, heralding an era of bio-inspired solutions that benefit both society and the planet.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025