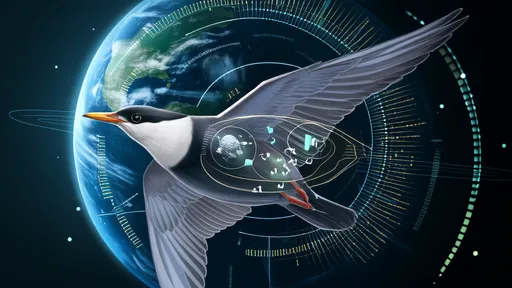

In the vast expanse of the natural world, few biological systems rival the precision and sophistication of raptor vision. These apex predators, including eagles, hawks, and falcons, possess visual capabilities that have been honed over millions of years of evolution, enabling them to detect, track, and capture prey with astonishing accuracy from incredible distances. The optical design underlying their high-precision tracking is a marvel of biological engineering, offering profound insights not only into avian physiology but also into potential applications in human technology, from advanced imaging systems to autonomous tracking devices.

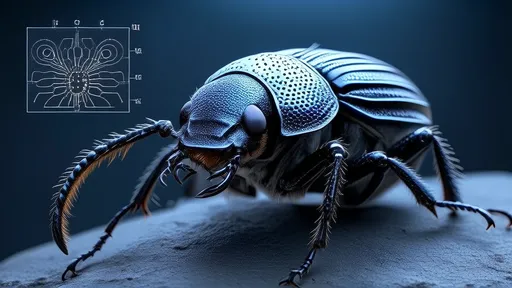

At the core of a raptor’s visual prowess is its exceptional spatial resolution. Eagles, for instance, are estimated to have visual acuity up to four times greater than that of humans. This means they can discern fine details at distances where humans would see only blurred shapes. Such resolution is achieved through a combination of factors: large eyes relative to head size, a high density of photoreceptor cells—particularly cones—in the retina, and a unique structural adaptation known as the fovea. Raptors often possess two foveae per eye, one for lateral vision and another for forward, binocular vision. The deep central fovea, in particular, is packed with photoreceptors and acts like a telephoto lens, magnifying the center of the visual field and providing the sharpness needed to spot a rabbit moving in the grass from hundreds of meters above.

Another critical element is the pecten, a comb-like structure found in the eyes of birds. While its exact functions are still debated, the pecten is believed to play a role in nourishing the retina and maintaining optimal optical performance by reducing shadows and scattering within the eye. This ensures that the image formed on the retina remains crisp and clear, even during high-speed maneuvers. Additionally, raptors have a higher flicker fusion rate than humans, meaning they can process rapid movements more smoothly—a vital trait for tracking erratically moving prey against complex backgrounds.

The design of the raptor eye also excels in dynamic tracking. Unlike human eyes, which have limited ability to lock onto moving targets without head movement, raptors can stabilize their gaze with incredible precision. This is due to specialized neuromuscular control systems that allow for minute, rapid adjustments of the eye position. Furthermore, their ability to perceive ultraviolet light adds another layer of discrimination, as urine trails or vole paths—visible in UV—stand out against the terrain, turning the landscape into a high-contrast map of potential prey activity.

Color vision in raptors is another area of sophistication. While many birds see a broader spectrum of colors than humans, raptors have optimized their color perception for hunting. They possess four types of cone cells, including those sensitive to violet and ultraviolet wavelengths, enabling them to detect contrasts and patterns that are invisible to other animals. This enhanced chromatic discrimination helps in identifying prey against camouflaged backgrounds and in assessing the health or ripeness of potential food sources from afar.

Perhaps one of the most fascinating aspects of raptor vision is its integration with neural processing. The optical information captured by the eye is processed by a brain that is exceptionally adept at interpreting motion and depth. The tectofugal pathway in the avian brain is highly developed, allowing for rapid computation of spatial relationships and movement vectors. This neural machinery works in tandem with the optical system to create a real-time, high-fidelity representation of the world, enabling raptors to predict the trajectory of prey and adjust their own flight path with split-second timing.

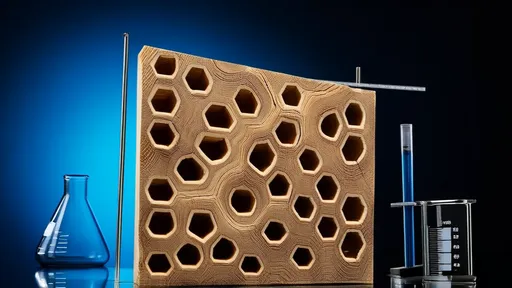

The principles underlying raptor vision have not gone unnoticed by engineers and designers. Biomimicry—the imitation of natural models—has led to innovations in surveillance cameras, drone navigation systems, and even sports broadcasting equipment. For instance, the dual-fovea concept has inspired the development of hybrid imaging systems that combine wide-angle views with high-resolution zoom capabilities. Similarly, algorithms that mimic the neural tracking of raptors are being used to improve object detection and following in autonomous vehicles and robotics.

In military and aerospace applications, the ability to track fast-moving targets with high precision is paramount. Research into raptor vision has informed the design of advanced targeting systems and optical sensors that can maintain focus on objects amid clutter and motion. By emulating the adaptive optics and processing strategies of these birds, engineers are creating systems that are more efficient, accurate, and resilient in challenging environments.

Despite these advances, replicating the full scope of raptor vision remains a daunting challenge. The integration of optics, neurology, and musculature in these birds is a product of eons of evolutionary refinement. Current technology struggles to match the energy efficiency, compactness, and multifunctionality of biological systems. However, ongoing research into materials science, artificial intelligence, and adaptive optics continues to narrow the gap, drawing ever closer to achieving artificial systems with the acuity and agility of a hawk’s eye.

In conclusion, the optical design of raptor vision represents a pinnacle of natural engineering, optimized for high-precision tracking in dynamic environments. Its blend of anatomical adaptations, spectral sensitivity, and neural integration offers a blueprint for next-generation optical technologies. As we deepen our understanding of these magnificent creatures, we not only unlock secrets of the natural world but also pave the way for innovations that could transform fields ranging from robotics to conservation. The eagle’s eye, once a symbol of keen sight, now guides the lens of human ingenuity toward new horizons.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025