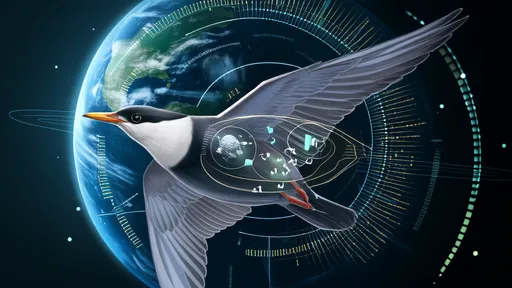

For decades, the mystery of how certain species navigate across vast and featureless landscapes has captivated scientists and laypeople alike. From the arctic tern’s pole-to-pole migration to the humble homing pigeon’s unerring return to its loft, these feats of biological navigation defy simple explanation. While behaviors like sun compass orientation and star navigation account for some of this ability, they fail to explain precise navigation on overcast days or in the absence of visual cues. The answer, it seems, may lie not in the macro world we perceive, but in the bizarre and counterintuitive realm of the quantum. A growing body of evidence suggests that a delicate, quantum-mechanical process—magnetoreception—is the secret behind nature’s most impressive navigators.

The primary hypothesis for a biological compass is known as the radical pair mechanism. This theory posits that certain molecules within an animal’s body can exist in a special, quantum state of superposition. When these molecules absorb light, typically blue or green wavelengths, an electron is excited and transferred, creating a pair of molecules each with an unpaired electron—a radical pair. Crucially, these two electrons are quantum entangled, meaning their spins are correlated regardless of the distance between them. The spins of these electrons are exquisitely sensitive to the Earth’s weak magnetic field. Depending on the angle of the magnetic field lines, the electron spins will oscillate between two quantum states, which in turn influences the ultimate chemical products formed by the radical pair. It is believed that specialized cells, potentially in the retina or elsewhere, can detect these subtle chemical changes, effectively allowing the animal to see or sense the magnetic field as a visual pattern or a visceral feeling overlaying its perception of the world.

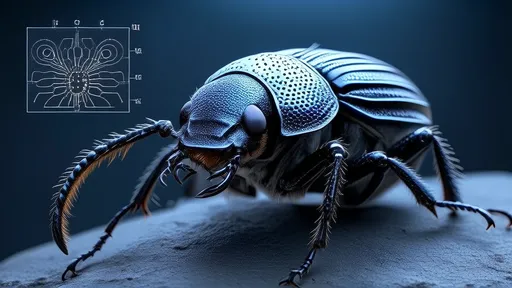

The search for the specific molecule responsible for this quantum feat has been a central pursuit in quantum biology. The leading candidate is a protein called cryptochrome, found in the photoreceptor cells in the eyes of birds, insects, and even some mammals. Cryptochrome is a flavoprotein that, upon absorbing light, forms the radical pairs necessary for magnetosensitivity. Experiments with genetically modified fruit flies, whose cryptochrome was replaced with the version from migratory birds, demonstrated a magnetic sense they did not previously possess. Even more astonishingly, disrupting the quantum coherence of the radical pairs—essentially causing a quantum decoherence event—erases the ability to orient to magnetic fields, providing compelling, albeit indirect, evidence that the mechanism is fundamentally quantum.

The implications of this research extend far beyond ornithology or entomology. If a biological system can harness quantum mechanics to sense something as faint as the planetary magnetic field, it forces a radical rethinking of the boundaries between the organic and the quantum worlds. Quantum processes were long thought to be too fragile, too susceptible to decoherence from the warm, wet, and noisy environments within living cells, to play a functional role in biology. The apparent existence of magnetoreception proves that evolution has found a way to protect and utilize quantum phenomena for a critical survival advantage. This discovery shatters the old dogma and opens the door to the possibility that other biological processes—perhaps even olfaction, enzyme catalysis, or neural processes—might have a quantum component.

This burgeoning field of quantum biology is not merely an academic curiosity; it holds immense potential for technological innovation. Understanding how nature builds a robust, energy-efficient, and exquisitely sensitive quantum sensor could revolutionize our own engineering approaches. The development of biomimetic quantum sensors for navigation is a prime example. Unlike traditional GPS, which relies on satellite signals that can be jammed, spoofed, or lost in tunnels and underwater, a magnetic navigation system would be perpetually available and impossible to disrupt externally. By mimicking the radical pair mechanism, scientists aim to create new generations of subminiature compasses for autonomous drones, submersibles, and personal navigation devices that operate with the reliability and precision of a migratory bird, without any need for external infrastructure.

Furthermore, the study of this biological quantum compass could provide invaluable insights for the broader field of quantum computing. One of the biggest challenges in building practical quantum computers is maintaining quantum coherence—keeping qubits in their delicate superposition state—long enough to perform calculations. Biological systems, as demonstrated by the radical pair mechanism, have naturally evolved to do just that within a complex cellular environment. Deciphering the biophysical tricks—be it through isolation, rapidity, or error correction—that organisms use to protect quantum states could provide blueprints for designing more stable and fault-tolerant qubits, bringing large-scale quantum computing closer to reality.

Of course, the field is not without its controversies and challenges. While the evidence for the radical pair mechanism is strong, it is not yet universally accepted as the sole explanation for magnetoreception. Other theories, such as one involving magnetic iron minerals like magnetite found in certain bacteria and animals, may work in concert with or independently of the quantum process. Isolating and directly observing the radical pairs in action within a living creature, without interfering with the process itself, remains a formidable technical hurdle. The next phase of research will require interdisciplinary collaboration between quantum physicists, biochemists, neurobiologists, and ethologists to move from compelling correlation to definitive causation.

In conclusion, the investigation into the quantum biological compass is a stunning example of how curiosity-driven science can unravel one of nature's oldest secrets and simultaneously point the way toward a new technological frontier. It bridges the gap between the seemingly abstract world of quantum physics and the tangible reality of a bird in flight. This research teaches us that the living world is not just based on chemistry, but might be deeply quantum at its core. As we continue to probe this interface, we are not only learning how a robin finds its way home; we are learning how to navigate the future of technology itself, guided by the subtle, quantum whispers of the Earth itself.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025