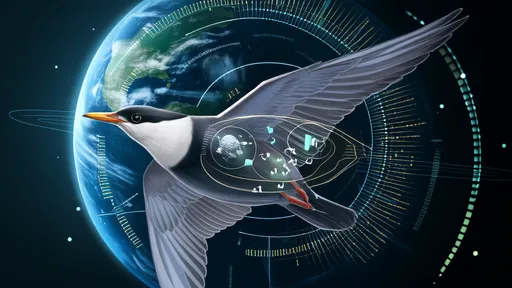

In the dense forests of Central America, a young songbird hesitantly mimics the melody of its father. Across continents in an Australian eucalyptus grove, a fledgling parrot practices the distinct contact calls of its flock. These are not mere repetitions but the foundations of cultural transmission—the phenomenon of avian dialects passing through generations like stories around a campfire.

For decades, ornithologists believed bird songs were largely innate, hardwired into their genetic code. But pioneering research by scientists like Peter Marler in the 1950s revealed something extraordinary: many bird species learn their songs through cultural transmission, much like human children acquiring language. This discovery opened a window into one of nature’s most sophisticated learning processes—vocal production learning in birds.

The process begins during a critical developmental period, often called the sensitive phase. During this window, young birds are exceptionally receptive to auditory inputs. They listen intently to adult tutors—usually their fathers or neighboring males—and form auditory templates of species-specific songs. This phase is followed by a period of vigorous practice, where juveniles produce subsong (akin to human babbling) before gradually refining their vocalizations through auditory feedback. The result? A culturally transmitted song dialect unique to their population.

Geographic isolation plays a crucial role in dialect formation. When populations of the same species become separated by mountains, rivers, or human infrastructure, their songs begin to drift apart. Over generations, these acoustic differences solidify into distinct regional dialects. White-crowned sparrows along the California coast, for instance, exhibit clear dialect boundaries between coastal and inland populations. Their songs—once homogeneous—now carry the unmistakable stamp of their cultural heritage.

But why do dialects matter? For birds, song is far more than aesthetic expression—it’s a vital tool for survival and reproduction. Males use songs to defend territories and attract mates. Females, in turn, often show preference for local dialects, suggesting that song matching serves as a proxy for genetic compatibility or local adaptation. In some species, like the zebra finch, females consistently prefer males singing familiar dialects, reinforcing cultural conformity within populations.

The social dynamics of avian communities further shape dialect evolution. In species with complex social structures, like parrots or corvids, young birds may learn from multiple tutors, leading to greater song diversity. Some species even exhibit dialect convergence—where neighboring groups gradually adopt similar vocal patterns, possibly to facilitate communication or reduce territorial conflicts. This cultural negotiation mirrors human linguistic phenomena like creolization or dialect leveling.

Human activities are now dramatically altering this ancient cultural tapestry. Urban noise pollution masks critical song frequencies, forcing birds to adjust their pitch or amplitude. Some species, like the great tit, have successfully adapted by shifting to higher frequencies. Others struggle, their songs drowned out by the rumble of civilization. Habitat fragmentation creates isolated populations, accelerating dialect divergence until some groups become culturally—and eventually genetically—distinct.

Climate change adds another layer of complexity. As species shift their ranges northward or to higher elevations, they encounter new vocal communities. The resulting cultural interactions—whether through hybridization or competitive exclusion—could reshape avian soundscapes in unpredictable ways. Some researchers speculate that climate-induced range shifts may lead to cultural erosion, where ancient dialects vanish as populations intermix or decline.

Conservationists are now recognizing the importance of preserving not just genetic diversity but cultural diversity as well. Dialects represent accumulated cultural knowledge—adaptations to local conditions that may prove crucial for survival. In New Zealand, conservation programs for the critically endangered kākāpō include efforts to maintain their distinct mating calls through audio playback of historical recordings. This cultural preservation may be as important as genetic management for species recovery.

Technological advances are revolutionizing how we study avian culture. Automated recording units deployed across landscapes capture millions of hours of birdsong, while machine learning algorithms detect subtle dialect variations invisible to the human ear. Researchers can now track cultural transmission in real-time, mapping how new song elements spread through populations like viral memes in human social networks.

The implications extend beyond ornithology. The study of bird dialects offers insights into the evolution of human language and culture. Both systems rely on vocal learning, social transmission, and the emergence of regional variations. Some researchers suggest that the same cognitive mechanisms underlying bird song learning—such as template matching and auditory feedback—may have paved the way for human speech evolution.

As dawn breaks over a misty forest, the air fills with a chorus of overlapping dialects—each song a thread in the rich cultural tapestry of avian life. These learned melodies carry more than individual identity; they embody generations of cultural heritage. In preserving these vocal traditions, we safeguard not just biological diversity but the living cultural history of our planet’s most accomplished vocal learners.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025