Each year, as seasons shift and temperatures begin to drop, an extraordinary phenomenon unfolds across continents. Billions of delicate wings take to the skies, embarking on journeys that span thousands of miles. The monarch butterflies of North America, the painted ladies of Europe, and the bogong moths of Australia—all partake in migrations that defy their fragile appearances. These tiny travelers, weighing less than a gram, navigate with precision across vast and unfamiliar landscapes, often arriving at destinations they have never seen. How do these minuscule creatures accomplish such formidable feats of navigation? The answer lies in a sophisticated interplay of innate biological mechanisms and environmental cues, a symphony of guidance systems that scientists are only beginning to fully understand.

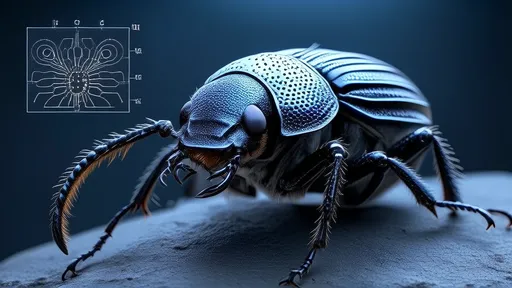

At the heart of insect migration is an internal compass, one that relies on the sun. Many migratory butterflies possess specialized photoreceptors in their eyes that can detect the sun’s position even on overcast days. They combine this solar reading with an internal circadian clock, allowing them to maintain a consistent direction regardless of the time of day. It’s as if they carry a built-in, sun-calibrated GPS that adjusts for the movement of the sun across the sky. This solar compass is remarkably robust, enabling them to stay on course through changing weather conditions and over long distances where landscapes offer few visual landmarks.

But the sun is not their only guide. On cloudy days or during twilight hours, many species switch to using the Earth’s magnetic field. Researchers have discovered that butterflies like the monarch contain cryptochrome proteins, which are sensitive to magnetic fields. These proteins, often located in the antennae or other parts of the body, act like a biological magnetometer, providing directional information when visual cues are scarce. This dual-system navigation—combining celestial and magnetic cues—ensures that migration continues uninterrupted, day or night, in clear skies or under cloud cover.

Yet direction is only part of the puzzle. Timing is equally critical. Migratory butterflies are exquisitely attuned to environmental signals that dictate when to begin their journeys. Decreasing daylight hours and falling temperatures trigger hormonal changes that prepare them for long-distance flight. These internal shifts prompt hyperphagia—a period of intense feeding to build fat reserves—and reproductive diapause, a suspension of breeding that allows them to focus energy on migration. It’s a finely tuned response to seasonal change, ensuring they depart precisely when conditions are most favorable for survival.

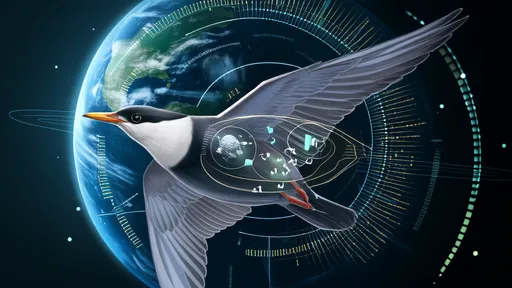

The routes these insects take are not random wanderings but well-defined pathways shaped by evolution and geography. Some, like the monarch butterflies, follow specific corridors that include stopover sites rich in nectar, essential for refueling. Others, such as the painted lady, exploit favorable wind currents to aid their journey, riding tailwinds that conserve energy and speed their progress. These routes are often inherited, passed down through generations not by learning but by genetic programming. Even individuals making the journey for the first time know exactly where to go and how to get there.

Perhaps the most astonishing aspect of these migrations is their multi-generational nature. For monarchs, the journey south is undertaken by a single generation that lives up to eight months—a Methuselah generation compared to their short-lived summer ancestors. These longer-lived butterflies navigate to specific overwintering sites, often the same groves of trees their great-great-grandparents used. After winter, they begin the return north, laying eggs along the way. Their offspring continue the journey, with each successive generation moving farther north until the cycle begins again. It’s a relay race across generations, with no single butterfly completing the full round trip yet the collective memory of the route preserved in their genes.

Human activity now poses significant threats to these ancient migratory pathways. Habitat loss, pesticide use, and climate change are disrupting the delicate balance these insects depend on. Monarch populations, for instance, have declined sharply due to the loss of milkweed—their sole host plant—and the degradation of their overwintering forests in Mexico. Changes in temperature and precipitation patterns are altering the timing of migrations, causing mismatches between the arrival of butterflies and the availability of nectar sources or host plants. The very cues they rely on, honed over millennia, are becoming unreliable in a rapidly changing world.

Conservation efforts are increasingly focused on protecting critical waypoints along these migratory routes. Initiatives like the creation of milkweed corridors across North America aim to provide essential resources for monarchs. International cooperation is also crucial, as these insects cross national borders with no regard for human politics. In Mexico, protected areas safeguard overwintering sites, while in Europe, efforts are underway to preserve meadows that serve as fueling stations for painted ladies. These actions recognize that the survival of migratory butterflies depends on the preservation of entire networks of habitats, not just isolated pockets.

Scientific research continues to unveil new layers of complexity in insect navigation. Recent studies suggest that some butterflies may also use polarized light patterns or even low-frequency infrasound to orient themselves. The role of learning, though minimal compared to birds or mammals, is not entirely absent; some evidence indicates that butterflies might adjust their routes based on experience. Each discovery adds another piece to the puzzle, revealing a navigation system that is both innate and adaptable, simple in its components yet breathtakingly sophisticated in its execution.

In the end, the migration of butterflies is more than a biological curiosity—it is a testament to the resilience and ingenuity of life. These tiny beings, with brains no larger than a pinhead, undertake journeys that dwarf human accomplishments in scale and difficulty. They connect ecosystems across continents, pollinating plants and sustaining food webs as they go. Their annual voyages are a reminder of the interconnectedness of our planet, a delicate thread of life that winds its way across mountains, rivers, and oceans. Protecting these migrations is not just about saving butterflies; it is about preserving one of nature’s most magnificent wonders for generations to come.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025