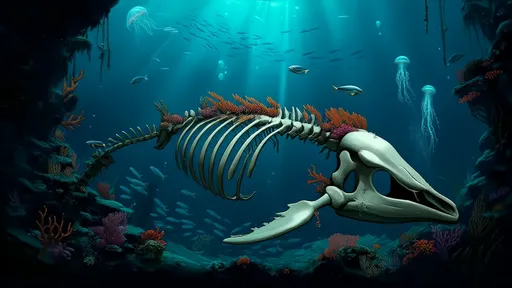

In the crushing darkness of the deep sea, where sunlight is a forgotten memory, a silent, spectacular light show perpetually unfolds. This is the realm of bioluminescence, a form of chemiluminescence where living organisms produce their own light through intricate chemical reactions. For the bizarre and often terrifying creatures that inhabit these depths, this biological innovation is not merely a curiosity; it is a fundamental tool for survival, a language, and a weapon, honed over millions of years of evolution in the planet's most extreme environment.

The fundamental chemistry behind this cold light is both elegant and widespread. The reaction typically involves a light-emitting molecule called a luciferin and an enzyme, luciferase. When luciferin reacts with oxygen, catalyzed by luciferase, it becomes electronically excited and then releases that energy in the form of a photon of light. The color of this light is often a soft blue or green, wavelengths that travel farthest in seawater. Some organisms, like the vampire squid, can even emit a red light or a cloud of glowing particles, a rarity in the deep-blue spectrum. This biochemical machinery is housed in specialized light organs called photophores, which can be simple or incredibly complex, equipped with lenses, filters, and shutters to control the intensity, direction, and pattern of the light emitted.

One of the most critical advantages bestowed by this self-made illumination is counter-illumination, a sophisticated form of camouflage. From below, the silhouette of a creature against the faint, down-welling light from the surface makes it an easy target for predators. Species like many squid, fish, and shrimp solve this problem with a row of photophores on their undersides. These organs precisely match the intensity and color of the ambient light from above, effectively erasing their shadow and rendering them invisible against the backdrop of the watery sky. This is an active camouflage, requiring constant adjustment, and represents a breathtaking evolutionary arms race between predator and prey.

Of course, light is also wielded as an offensive weapon. The anglerfish is the classic example, using a bioluminescent lure, or esca, dangling from a modified fin ray above its monstrous jaws to attract curious prey directly into its waiting mouth. Other hunters, like the stoplight loosejaw dragonfish, utilize a unique trick. They produce a beam of red light, a color most other deep-sea creatures cannot perceive. This allows them to illuminate their prey like a sniper using a night-vision scope, striking without being detected. For some, light is a tool for distraction or defense. When threatened, a shrimp may release a glowing cloud, similar to the ink squid eject at the surface, creating a bright, confusing smokescreen to baffle a predator and facilitate a swift escape.

Beyond the dynamics of eating and avoiding being eaten, bioluminescence serves as a complex communication system. In the perpetual night, finding a mate is a significant challenge. Many species have evolved specific, species-specific flashing patterns to advertise their presence and readiness to reproduce. The famous "string of pearls" display of the female fireworm or the synchronized flashing of certain plankton are essentially love letters written in light, ensuring that individuals can find and recognize suitable partners of their own kind amidst the vast, empty darkness. These signals must be precise; a wrong flash could attract a predator instead of a mate.

The evolutionary journey to this point is a story of remarkable ingenuity. It is widely believed that bioluminescence first evolved as a means to deal with oxygen toxicity in the early, anoxic oceans. The luciferin-luciferase reaction effectively neutralizes dangerous oxygen free radicals, a fortunate byproduct of which was light. Organisms that could capitalize on this accidental light for a survival advantage—perhaps to startle a predator or attract prey—thrived. Over eons, natural selection refined this chemical accident into the precise and diverse toolkit we see today. This involved not just the refinement of the chemistry itself, but the development of the complex organs to house it and the neural pathways to control it with exquisite precision.

The study of deep-sea bioluminescence is notoriously difficult, requiring remote-operated vehicles and sensitive cameras to glimpse this hidden world without disturbing it. Yet, each expedition reveals new wonders and complexities. Scientists are now looking to these creatures for inspiration in fields like medical imaging, where new luciferases can be used as reporter genes to track the progression of diseases like cancer within the body. The efficiency of this cold light production is also a model for developing new, energy-efficient lighting technologies. The deep sea, once thought to be a biological desert, is proving to be a treasure trove of biochemical innovation.

In conclusion, the evolution of bioluminescence in the deep sea is a profound testament to life's adaptability. What may have begun as a simple cellular detoxification process has been shaped by immense evolutionary pressures into a multifaceted survival strategy. It is a language of light spoken in the dark, a dance of deception and discovery that governs life in the abyss. For the creatures of the deep, their self-generated glow is the difference between life and death, between finding a meal and becoming one, between perpetuating their species and fading into eternal blackness. This chemical illumination is not just a biological feature; it is the very currency of existence in the world's final frontier.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025