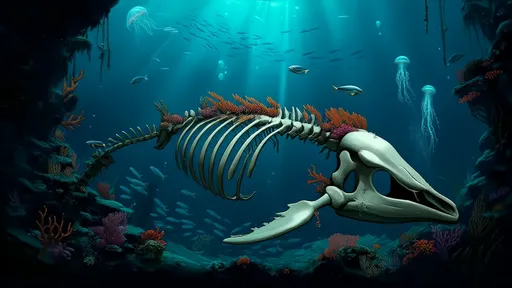

Beneath the sun-dappled waves of our planet’s oceans lies one of nature’s most intricate and vital partnerships: the coral holobiont. This complex symbiotic system, composed of the coral animal, photosynthetic dinoflagellates, and a diverse array of bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses, functions as a cohesive meta-organism. For decades, scientific inquiry has rightly focused on the relationship between corals and their algal symbionts, Zooxanthellae, which provide up to 90% of the host’s energy requirements through photosynthesis. However, a silent, microscopic workforce operating within and upon the coral has long been overlooked. The coral microbiome, a dynamic consortium of microorganisms, is now emerging from the shadows of its more famous partners, recognized not as mere passengers but as fundamental architects of coral health, resilience, and ultimately, the survival of entire reef ecosystems.

The ecological regulation performed by the coral microbiome is nothing short of astonishing in its scope and sophistication. This microbial community forms a critical interface between the coral host and its environment, acting as a first line of defense, a metabolic factory, and an environmental sensor all at once. A primary function is pathogen resistance. The microbiome occupies ecological niches on the coral’s surface, effectively creating a protective shield. Beneficial bacteria produce a cocktail of antimicrobial compounds, antibiotics, and enzymes that directly inhibit the colonization and proliferation of opportunistic pathogens like Vibrio species. This phenomenon, known as colonization resistance, is a classic ecological process, and its failure can lead to the onset of devastating diseases like white syndrome and black band disease. The microbiome, therefore, is the coral’s innate immune system, a living, evolving pharmacy that tailors its defenses to local threats.

Beyond defense, the microbiome is an indispensable metabolic partner, filling nutritional gaps and recycling essential elements in a nutrient-poor environment. While the zooxanthellae are masters of carbon fixation, the microbial partners are crucial for nitrogen cycling. Specific bacteria, including cyanobacteria, can perform nitrogen fixation, converting inert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia, a usable form of nitrogen that fertilizes the entire holobiont. Other microbial groups are adept at processing the host’s waste products, such as recycling urea and ammonium, and participating in the sulfur and phosphorus cycles. This intricate metabolic network ensures that precious nutrients are retained and efficiently reused within the holobiont, reducing the coral’s dependence on external food sources and allowing it to thrive in crystal-clear, oligotrophic waters.

Perhaps the most critical role of the microbiome in the modern era is its contribution to environmental stress resilience, particularly thermal tolerance. As ocean temperatures rise due to climate change, corals undergo bleaching—a stress response where they expel their zooxanthellae, turning white and risking starvation. Research now reveals that the microbiome is not a passive victim in this process but an active mediator. Certain bacterial taxa are known to produce antioxidants and other protective molecules that mitigate the cellular damage caused by heat stress. Furthermore, evidence suggests that corals can dynamically alter their microbial composition in response to environmental cues, a process termed microbial priming or acclimatization. A coral that has experienced mild previous heat stress may assemble a microbiome enriched with heat-tolerant and protective bacteria, effectively ‘learning’ to cope with higher temperatures. This plasticity offers a glimmer of hope, suggesting a mechanism for rapid, non-genetic adaptation that could buy time for corals in a warming world.

However, this delicate regulatory system is highly vulnerable to disruption. The same anthropogenic pressures that cause coral bleaching—climate change, pollution, and coastal development—also severely dysregulate the coral microbiome. Pollution from agricultural runoff, rich in nutrients and contaminants, can fertilize the growth of opportunistic, harmful microbes, destabilizing the community and leading to a state of dysbiosis. In dysbiosis, the protective and beneficial functions break down, and the microbiome can itself become a source of pathology. Climate change-induced heatwaves can cause a collapse of core microbial functions, pushing the holobiont past a tipping point from which it cannot recover. This dysbiosis often precedes visible signs of bleaching or disease, making the microbial community a critical early-warning signal for reef health.

The profound understanding of the microbiome’s regulatory role is now paving the way for novel conservation strategies. The old paradigm of simply protecting reef geography is expanding to include protecting and even manipulating microbial life. Probiotic therapy for corals is a burgeoning field of research. Scientists are isolating beneficial, stress-resistant bacteria from healthy corals and applying them to stressed or juvenile corals in lab settings and nurseries to boost their resilience before outplanting them to degraded reefs. This approach aims to actively engineer healthier holobionts. Similarly, the concept of microbial rescue involves identifying reefs that host corals with naturally resilient microbiomes and prioritizing their protection as potential reservoirs of beneficial microbes that could aid in the recovery of adjacent degraded areas.

In conclusion, the narrative of coral symbiosis has been rewritten. The coral is not an animal with algae living in it; it is a complex ecosystem, a republic of species working in concert. The microbial partners are the unseen regulators of this republic, governing health, metabolism, and adaptation. Their ecological functions are the bedrock upon which coral reef survival rests. As we confront an era of unprecedented environmental change, acknowledging and harnessing the power of the coral microbiome may be our most promising tool in the race to preserve the breathtaking biodiversity and essential ecosystem services of the world’s coral reefs. The fate of these underwater cities is inextricably linked to the smallest of their inhabitants.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025