In the intricate dance of predator and prey, few hunters match the precision of the praying mantis. These seemingly placid insects, often mistaken for serene vegetarians, are in fact formidable predators equipped with one of the most sophisticated visual processing systems in the invertebrate world. Their success hinges not on brute force or overwhelming speed, but on a breathtakingly accurate calculation of distance—a real-time, three-dimensional assessment of their world that guides their iconic, lightning-fast strikes. This capability, known as stereopsis or stereoscopic vision, transforms their two-dimensional visual inputs into a rich depth map, allowing them to pinpoint the exact location of unsuspecting prey with unerring accuracy.

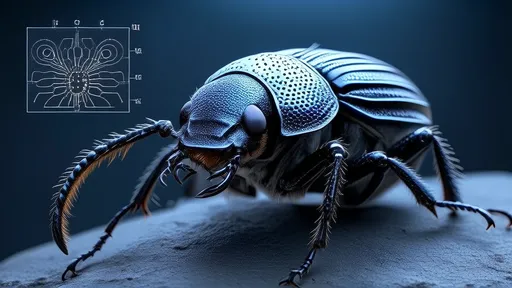

For decades, the mantis has been a subject of fascination not just for entomologists but for neuroscientists and engineers alike. The fundamental question is how an animal with a brain the size of a grain of rice performs complex computations that challenge even our most advanced computers. Unlike humans and other primates, whose forward-facing eyes provide overlapping fields of view essential for depth perception, the mantis possesses a vastly different ocular architecture. Its two large, bulbous compound eyes are positioned on the sides of its triangular head, offering an almost 360-degree view of its surroundings. This panoramic vision is excellent for detecting motion from any direction, a crucial early-warning system against its own predators. However, the critical region for depth perception is a narrow band where the visual fields of these two eyes overlap directly in front of the insect. It is within this small window of binocular overlap that the magic of stereoscopic vision occurs.

The underlying mechanism is a neurological process of breathtaking elegance. Each compound eye captures a slightly different two-dimensional image of the world. These two separate images are transmitted via the optic nerve to the central nervous system. Here, specialized neurons act as correlation detectors. Their sole function is to identify specific features—like a dark spot representing a fly’s wing—in the image from the left eye and then hunt for that same feature in the image arriving milliseconds later from the right eye. The computational genius lies in measuring the disparity or the positional difference of that feature between the two images. A large disparity indicates the object is close; a small disparity means it is farther away. The brain effectively triangulates the distance to the target based on this retinal shift, creating an instantaneous and precise depth map.

This biological system is a masterclass in efficiency. The mantis brain does not process the entire scene in high resolution. Instead, it likely focuses its stereoscopic calculations on areas of high contrast or movement—the tell-tale signs of potential prey. This selective processing conserves immense amounts of neural energy, allowing for a rapid response without cognitive overload. Research involving mantises wearing tiny 3D glasses has spectacularly confirmed this. Scientists can project moving stimuli onto screens, and the insects will strike at virtual prey only when the images presented to each eye contain the correct binocular disparity for depth. This proves that their strikes are not simple reflexes triggered by motion but are deliberate actions guided by a computed perception of three-dimensional space.

The implications of understanding the mantis's visual system extend far beyond basic biology. In the field of robotics and computer vision, engineers face a constant challenge: enabling machines to perceive depth quickly, accurately, and without consuming vast computational power. Current methods like LiDAR or complex stereo camera setups are effective but often energy-intensive and computationally expensive. The mantis offers a blueprint for a different approach—a lean, efficient algorithm that focuses on specific, relevant cues rather than processing an entire environment. By reverse-engineering the neural circuitry of the mantis, researchers aim to develop new algorithms for depth perception in robots, drones, and even autonomous vehicles. These systems could navigate cluttered environments by identifying key obstacles and calculating distances with the efficiency of an insect, a revolutionary step forward in machine autonomy.

Furthermore, the study of mantis stereopsis provides profound insights into the evolution of vision itself. It demonstrates that advanced stereoscopic vision is not the exclusive domain of large-brained mammals. It evolved independently in the insect lineage, a stunning example of convergent evolution where entirely different neural architectures arrive at the same sophisticated solution to a universal problem: judging distance. This suggests that the computational principles of depth perception may be a fundamental and highly efficient strategy that can be implemented by even the most minimal of neural hardware. Understanding these ancient and optimized algorithms helps scientists piece together the evolutionary pressures that shaped perception and could reveal core principles of neural computation applicable across the animal kingdom.

In the end, the praying mantis is far more than a garden curiosity; it is a living testament to the power of evolutionary innovation. Its ability to calculate the world in three dimensions with a microscopic brain is a humbling reminder that complexity does not always require size. Every precise, successful strike is the result of millions of years of refinement—a perfect synergy of optics, neurology, and physics. As we continue to decode its secrets, we are not only learning about an insect; we are uncovering fundamental principles of perception that inspire new technologies and deepen our appreciation for the elegant solutions engineered by nature.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025