In the grand theater of evolution, few forces have sculpted life’s diversity with such flamboyant precision as sexual selection. While natural selection favors traits that enhance survival—the sharpest claws, the swiftest legs—sexual selection operates on an entirely different principle: the often extravagant, sometimes bewildering, and always fascinating aesthetics of attraction. This is the engine behind what can only be described as an aesthetic revolution in the natural world, a process driven not by the harsh logic of survival, but by the nuanced and powerful preferences of choosy mates.

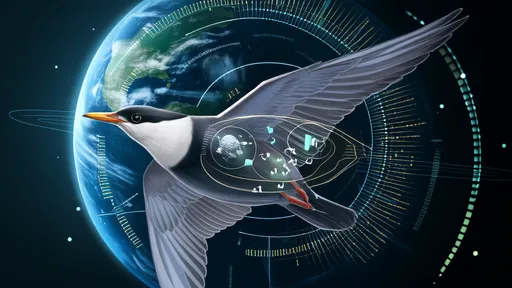

The concept was first rigorously explored by Charles Darwin, who found himself puzzled by features that seemed to contradict his theory of natural selection. The magnificent, cumbersome tail of the peacock; the elaborate songs of certain birds; the dramatic antlers of a stag—these traits appeared to be handicaps, consuming vital energy and making their bearers more visible to predators. Darwin proposed a supplementary theory: these traits evolved because they are attractive to the opposite sex. An individual with a spectacular tail, though it might be slightly more vulnerable, gains a massive advantage in reproduction. Its genes, including the genes for that very tail, are passed on, shaping the next generation.

This process creates a powerful feedback loop, often referred to as Fisherian runaway selection. It begins with an initial, perhaps arbitrary, preference. If female birds, for instance, show a slight preference for males with longer tails, those males will enjoy greater mating success. Their sons will inherit both the longer tails and the predisposition to prefer them. Their daughters will inherit the stronger preference for long tails. Over generations, this can lead to an explosive, "runaway" exaggeration of the trait far beyond what seems practical, resulting in the breathtaking plumage we see today. The aesthetic standard becomes encoded in the genes, a beautiful trap from which the species cannot easily escape.

But these displays are rarely just empty beauty. In many cases, they function as honest signals of underlying quality. Producing a brilliant feather display or a complex song requires significant resources—excellent nutrition, a robust immune system, and freedom from parasites. A male who can manage such a flamboyant handicap is, by definition, a high-quality individual. He is effectively advertising his superior genetic fitness. The peahen, by choosing the male with the most eyespots on his train, is not merely selecting for beauty; she is making a shrewd investment in the health and viability of her offspring. The aesthetic, therefore, becomes a reliable indicator of Darwinian fitness.

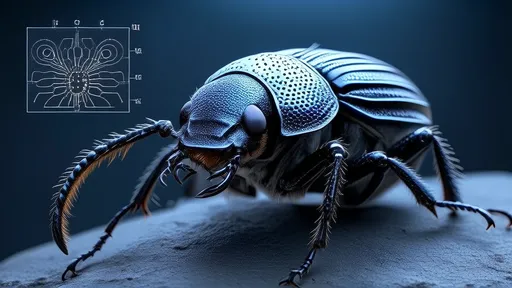

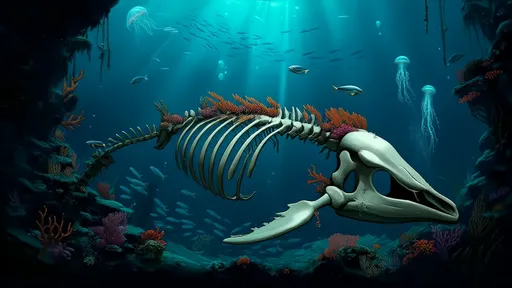

The manifestations of this aesthetic arms race are as diverse as life itself. In the bird-of-paradise, it results in impossible dances and iridescent plumes that seem to defy physics. In the humpback whale, it produces complex, evolving songs that travel across entire ocean basins. In the fiddler crab, one claw grows to a monstrous size, becoming a tool for both threat and courtship. In humans, this same evolutionary pressure may have shaped our appreciation for symmetry, creativity, and even moral virtue—traits that signal a good partner and parent. Art, music, and storytelling could be seen as our own species' unique and incredibly sophisticated form of courtship display, a testament to the power of sexual selection to drive cultural as well as biological evolution.

This revolution in aesthetics has profound implications beyond biology. It challenges our perception of beauty as a mere social construct or a trivial pleasure. The awe we feel when confronted with the vibrancy of a coral reef fish or the intricate pattern of a spider's web is not accidental; it is a deep, evolved response to signals of vitality and creativity. It suggests that our own pursuit of art and beauty is not a frivolous departure from the serious business of survival, but is instead woven into the very fabric of our evolutionary history. We are the products of countless generations of choosy ancestors, and their preferences have made us who we are.

Ultimately, the world we see around us—its colors, sounds, and forms—is a living gallery, curated by the most powerful and enduring of art critics: the imperative to reproduce. The aesthetic revolution driven by sexual selection reveals a universe where beauty is not just in the eye of the beholder, but is a fundamental, dynamic, and potent force in the evolution of life on Earth.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025