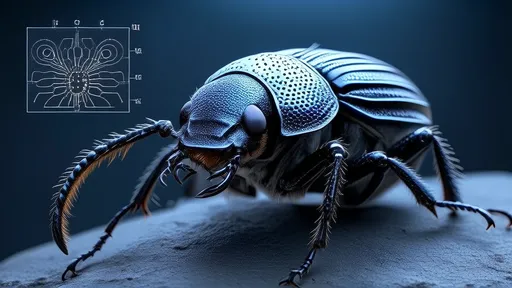

In the dense undergrowth of a tropical rainforest, a rhinoceros beetle lifts an object 850 times its own weight—a feat equivalent to a human hoisting two fully loaded semi-trucks. This staggering display of strength is not powered by bulging muscles but by an evolutionary masterpiece: the exoskeleton. For centuries, the armored shells of beetles have been casually dismissed as nature’s plate mail, mere protective casings. But to materials scientists and engineers, they represent one of the most sophisticated and optimized structural materials on the planet. The study of the beetle exoskeleton has evolved from biological curiosity to a frontier of interdisciplinary research, where zoology meets cutting-edge materials science, promising to revolutionize how we design everything from aircraft to body armor.

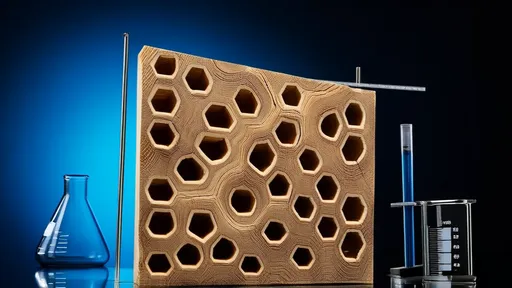

The exoskeleton, or cuticle, of a beetle is a complex composite material, a masterpiece of nano-engineering forged over 300 million years of evolution. It is not a single, homogenous shell but a layered structure, each tier serving a distinct mechanical and biological function. At its most fundamental level, it is composed of chitin polymer chains—long, fibrous molecules—embedded in a matrix of proteins. This combination alone provides a remarkable strength-to-weight ratio. However, evolution has further refined this base recipe. The secret lies in the hierarchical organization. Chitin molecules self-assemble into nanofibers, which bundle together to form larger fibers. These fibers are then arranged in a helicoidal pattern, much like the layers of plywood, each layer rotated slightly from the one below it.

This helicoidal arrangement is a stroke of evolutionary genius. It creates a material that is exceptionally tough and resistant to fracture. When a force is applied, the rotated layers help to distribute the stress throughout the structure, preventing the formation of large cracks. Instead of shattering catastrophically, the material may deform or allow small, contained cracks to form, absorbing immense energy in the process. This is a critical advantage for a beetle, which might face impacts from falling debris, pecks from predators, or the intense pressures of burrowing. This natural damage tolerance is a property that engineers desperately seek to replicate in synthetic composites, which often fail in brittle, unpredictable ways.

Beyond its base composite structure, the exoskeleton is a multifunctional system with properties fine-tuned to the specific life history of each beetle species. A diving beetle, for instance, has a cuticle optimized for hydrodynamics and resisting constant water pressure, while a desert-dwelling darkling beetle has a texture that maximizes water collection from morning fog. The mechanical properties are not uniform across the entire shell. Areas requiring high flexibility, such as the joints between body segments and limbs, have a different protein composition and fiber orientation, creating a flexible membrane akin to biological rubber. In contrast, the mandibles, designed for cutting and crushing, are heavily mineralized with calcium carbonate and zinc, transforming them into hardened, wear-resistant tools.

This precise spatial control over material properties is a level of manufacturing sophistication that human industry is only beginning to approach with technologies like 4D printing and functional grading. The beetle does not assemble its exoskeleton in a factory; it grows it from the inside out, using cellular processes to precisely control the deposition of chitin and proteins, creating a seamless integration of hard and soft, rigid and flexible. This bio-fabrication process is energy-efficient and occurs at ambient temperatures and pressures, a stark contrast to the energy-intensive, high-heat processes required to manufacture advanced carbon composites or ceramics.

The potential applications inspired by the beetle exoskeleton are as vast as they are transformative. In the aerospace and automotive industries, where every gram saved translates to massive gains in fuel efficiency and reduced emissions, the development of new, lighter, and tougher composite materials is paramount. By mimicking the helicoidal architecture of the cuticle, researchers are developing next-generation composites that are significantly more impact-resistant than current carbon-fiber laminates. These bio-inspired composites could lead to lighter aircraft wings, more durable car frames, and safer, more efficient turbine blades.

Perhaps the most direct application is in the field of personal protective equipment. Modern body armor, often based on rigid ceramic plates and woven para-aramid fibers (like Kevlar), faces a constant trade-off between protection, weight, and mobility. A suit of armor inspired by the beetle’s exoskeleton could revolutionize this field. Imagine a vest that uses a layered, helicoidal structure to dissipate the energy of a bullet impact more effectively, preventing blunt force trauma while being lighter and more flexible than current systems. This would provide soldiers and police officers with unparalleled protection and mobility, potentially saving countless lives.

The field of robotics is also poised for a bio-inspired revolution. Traditional robots, built from hard metals and plastics, are often clumsy and inefficient in unstructured, natural environments. Soft robotics aims to change that, but integrating strength into soft materials remains a challenge. The beetle’s exoskeleton, with its graceful integration of rigid and flexible elements, provides the perfect blueprint. Researchers are developing robotic exoskeletons and limbs that mimic this design, creating machines that are both strong and compliant, capable of delicate tasks as well as feats of strength. These robots could be used for disaster response, exploration, or even as advanced prosthetics that closely mimic the movement and resilience of natural limbs.

Despite the exciting progress, translating nature’s blueprint into manufacturable technology presents immense challenges. We can observe the structure of the exoskeleton with powerful microscopes and simulate its behavior with complex computer models, but replicating the precise self-assembly processes that occur at the nanoscale is incredibly difficult. Current manufacturing techniques, such as 3D printing, are only just beginning to achieve the resolution needed to imitate these hierarchical structures. Furthermore, the exoskeleton is a living material, capable of self-repair to a certain extent—a feature far beyond the reach of today’s synthetic materials. The future of this field may lie not in directly copying the structure, but in understanding the fundamental principles of its growth and self-organization, potentially leading to entirely new manufacturing paradigms where materials are grown to shape with embedded functionality.

The humble beetle, often seen as a mere garden visitor or pest, is in reality a walking testament to the power of evolutionary optimization. Its exoskeleton is a material that has been refined for millions of years to achieve a perfect balance of strength, toughness, lightness, and multifunctionality. As scientists continue to decode its secrets, they are not just learning about biology; they are uncovering a new philosophy of design. This bio-inspired approach moves away from the traditional, often wasteful, methods of engineering and towards a more integrated, efficient, and sustainable model. The beetle’s shell is more than armor; it is a textbook, a guidebook, and a blueprint for the next generation of advanced materials, promising to build a stronger, lighter, and more resilient future.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025